Spatial Data Trusts

What are they and why might they be important to you?

Digital spatial data has transformed our society today. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a digital future without spatial data at its core.1 Yet our ability to share spatial data consistently lags far behind the many applications and demonstrated needs for this data. Sharing of spatial data remains one of the most longstanding and intractable challenges facing spatial data scientists and data custodians. The barriers to sharing are sometimes technical (e.g., the formats, volume, and complexity of spatial data). More often, however, the stubborn barriers to sharing are not (only) technical. Rather they concern data governance, such as understanding the quality and fitness-for-use of spatial data; managing the risks, liability, security, and licensing associated with sharing; and safeguarding individual location privacy and data sovereignty.

This is where Data Trusts come in…

What is a Data Trust?

A Data Trust is a legal and technical framework for independent stewardship of data that helps promote data sharing. In short, a Data Trust combines the technical infrastructure for sharing data with the governance framework of a legal trust.

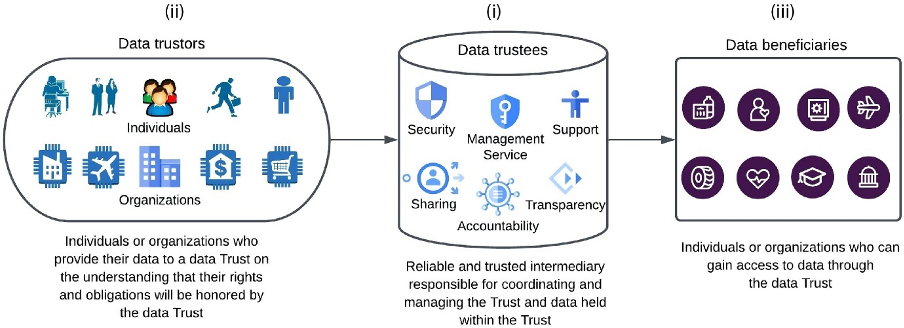

Any Data Trust involves three main parties:

data beneficiaries are individuals or organisations who stand to benefit from using data that might otherwise be unavailable;

data trustors are individuals or organisations who can allow wider access to their data, given certainty that their rights to the data will be respected and the risks of sharing will be carefully managed; and

data trustees are reliable groups or organisations who can act as independent mediators between data trustors and data beneficiaries, to help unlock data that might otherwise remain siloed.

Through this structure, Data Trusts aim to provide clear, appropriate, fair, and transparent rules to guide decisions about data sharing. The rules for a Data Trust are overseen by a board of trustees charged with protecting the rights associated with data, and backed by legal (or at least quasi legal) assurances.2

Who is using Data Trusts?

In last few years, Data Trusts have begun to establish themselves across a growing range of different industry sectors. Perhaps unsurprisingly, some of the earliest adopters are found in the health sector, where increased sharing of data can literally save lives, but data security and privacy remain of overriding importance. Data Trusts such as Open Humans, John Hopkins Institute, and the Silicon Valley Regional Data Trust help enable sharing of medical data, at the same time as managing security, privacy, and acceptable use of that data.

Data Trusts in the public interest are emerging in civil society too, such as The Commonwealth Data Trust, Worker Info Exchange, DATA TRUST, and Food Data Trust. In the finance sector, Data Trusts such as TRUATA provide hosting, data anonymisation, and protection of personal financial data compliant with European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), as well as supporting data analytics that helps unlock untapped value in data.

The Data Trust model has particular relevance for Indigenous data sovereignty. For example, managed by the Bourke Tribal Council in Australia and supported by Seer Data & Analytics, the Maranguka Community Hub brings together diverse data to support improved decision making in the community, while safeguarding the rights of the Indigenous people connected with that data.

Most recently, the first Data Trusts with a focus on spatial data have started to emerge. Amongst the first, the PLACE Data Trust, formed by the Omidyar Network, focuses on collecting, managing, protecting, and sharing high-resolution imagery captured by drones and commercial street camera systems. The Trust provides services to its members including technical, educational, and financial support for aerial drone mapping; aggregation and storing of imagery data; and administering membership, licences, and fees. PLACE does not own the collected data, although a copy of all data is securely stored within the Trust.

Such nascent initiatives lead naturally to the question, “What does the Data Trust model mean for spatial data?”

What makes Spatial Data Trusts special?

Our recent academic research paper on Spatial Data Trusts goes in to detail about what the Data Trust model may mean for spatial.3 But the key question at the root of that research is, What makes Spatial Data Trusts special? For those researchers, organisations, companies, communities, and individuals working to promote spatial data sharing specifically, what are the challenges (and opportunities) faced?

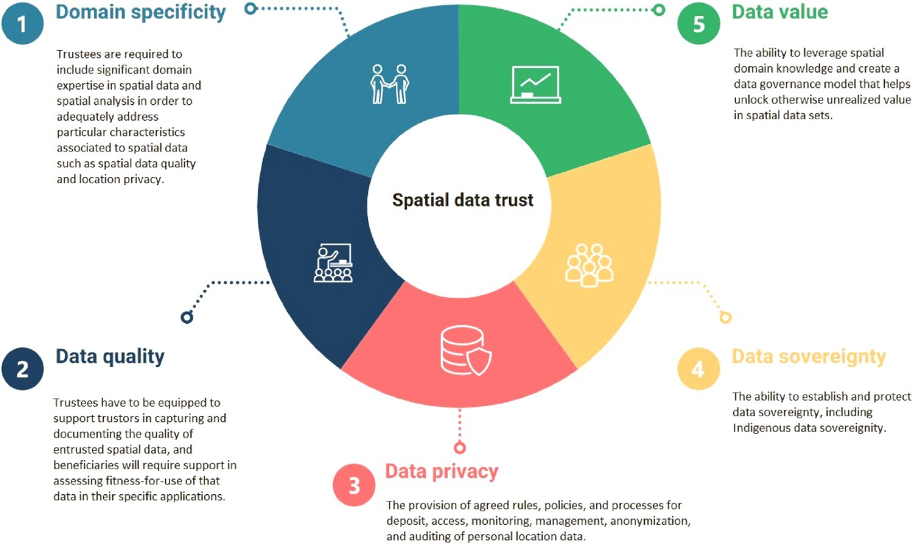

In our answer to this question, we identified five essential features of a Spatial Data Trust that require special attention.

Domain specificity: Spatial data is complex. That means managing, protecting, and sharing spatial data usually requires active involvement spatial professionals. For example, understanding spatial data formats, capture, and technologies benefits from the availability of expert spatial knowledge. As a result, a Spatial Data Trust will likely need to include spatial domain expertise on its a board of trustees.

Data quality: Spatial data is always uncertain. No matter how good your data sources, how careful your data capture, or how up-to-date your data, spatial data is always—to some extent—wrong.4 This inherent uncertainty creates risk. For example, we’re used to relying on spatial data about our roads and traffic to direct our taxi driver, route a delivery, or to get us to work on time. But does that mean you would want with your ambulance driver or emergency responder relying on that same data? Understanding the quality of spatial data, and its fitness-for-use, is complex, especially in an era of crowdsourced, user-generated data. Every Spatial Data Trust will need to manage spatial data quality.

Data privacy: Spatial data is often accompanied by privacy concerns. A person’s precise location uniquely identifies them, and can potentially be used to make intrusive inferences about who they are, who they know, what they believe, what they enjoy, and to otherwise intrude into their lives. Managing location privacy is complex, as attested past high-profile examples of serious, if inadvertent, privacy breaches.5 A Spatial Data Trust needs to include the expertise to ensure the safety and protection of personal location information—for data trustors as well as the people whose privacy might be impacted by a mistake.

Data sovereignty: Spatial data is a part of our critical digital infrastructure. As such, many spatial data sets around the world have implications for national security. Spatial data is no less important to nation states than to First Nations. The rights of Indigenous people to control data about their knowledge, land, and communities is at the core of Indigenous data sovereignty, as already mentioned. Spatial Data Trusts, then, require the ability to manage spatial data sovereignty in all its complexity and diversity.

Data value: Spatial data is valuable. Indeed, the impetus behind innumerable and decades-long spatial data sharing initiatives around the world—undoubtedly costing in aggregate billions of dollars and arguably generating many times that benefit in return—arises from the need to maximise that value. Yet, today we still have a poor understanding and management of the value of spatial data. We think Spatial Data Trusts may hold the key to unlocking untold, unrealised value in spatial data sets, inaccessible to most of us today.

Author note

This post is based on a recent academic research paper by the authors, below. We welcome feedback, discussion, and comments. (Most authors are contactable on LinkedIn and Twitter, as well as directly on email).

Radosevic, Duckham, Rahaman, Ho, Williams, Hashem, and Tao (2023) “Spatial data trusts: an emerging governance framework for sharing spatial data”, International Journal of Digital Earth, 16(1), 1607–1639. doi:10.1080/17538947.2023.2200042

If you need any convincing of just how pervasive spatial data is, just take a look at your smartphone’s location preferences, and count how of many of your installed apps rely on accessing your location!

Delacroix and Lawrence (2019) “Bottom-up data Trusts: disturbing the ‘one size fits all’ approach to data governance”, International Data Privacy Law, 9(4): 236–252. doi:10.1093/idpl/ipz014

Radosevic, Duckham, Rahaman, Ho, Williams, Hashem, and Tao (2023) “Spatial data trusts: an emerging governance framework for sharing spatial data”, International Journal of Digital Earth, 16(1), 1607–1639. doi:10.1080/17538947.2023.2200042

Although other domains do grapple with uncertainty in data, many do not. You would (rightly) not accept it if your bank told you they were not exactly sure how much money was in your bank account. Yet, you will need to accept that your local government will never be able to tell you exactly where your house is located.

https://ovic.vic.gov.au/mediarelease/information-commissioner-investigates-breach-of-myki-users-privacy/