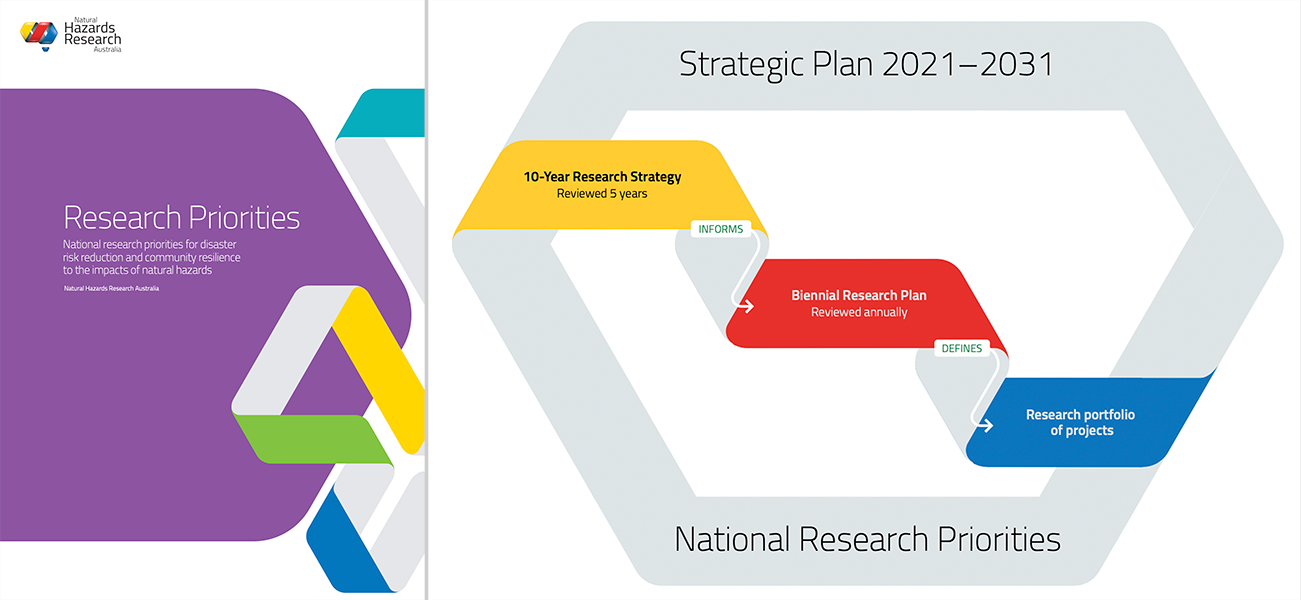

Natural Hazards Research Australia (NHRA) was established by Australian Government funding in 2021 as the new national centre for research collaboration in connection with natural hazards. Over the past year, activity has been steadily increasing at NHRA and at the end of May 2022, NHRA released a new report that sets out its national Research Priorities for the coming decade (NHRA Research Priorities).

The NHRA positions its report carefully in the context of other influential reports over recent years, nationally and internationally. The report draw strongly on the Sendai Framework, the 2012 National Strategy for Disaster Resilience, the 2018 National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework, the 2020 Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements, and more broadly on the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

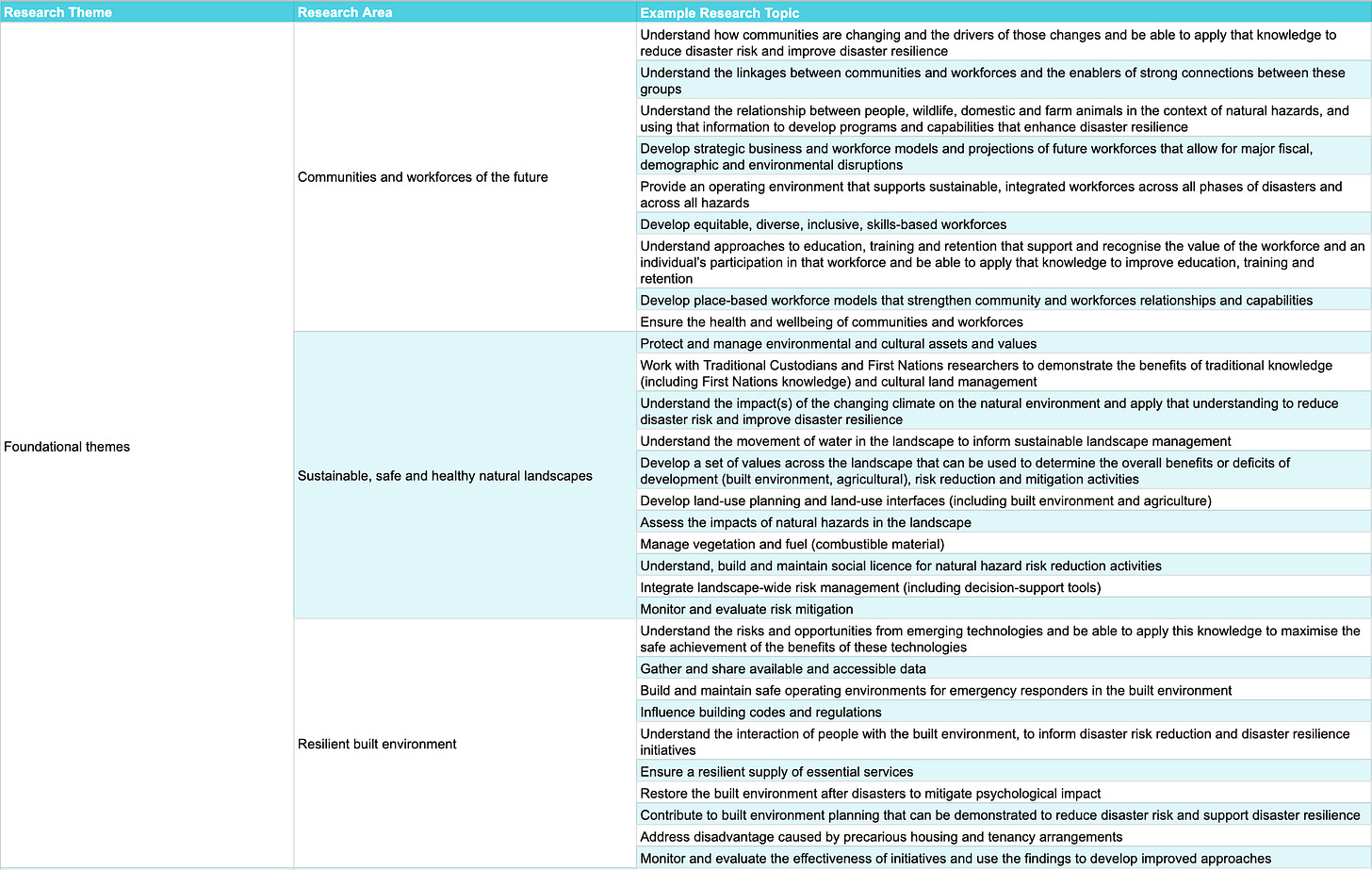

The research priorities themselves are organised into eight research areas, grouped into three research themes:

The first theme, foundational research, encompasses fundamental research in disaster resilience and risk reduction for communities and workforces, for sustainable natural environments, and for resilient built environments.

In the second theme, functional research, resilient communities again feature strongly as one of the three research areas. It is tricky to tease apart what exactly makes the difference between community resilience as foundational versus functional themed research. However, the other two areas under the functional theme, situational awareness and operational response, are indicative of a more practical and applied focus in the functional, when compared with the foundational theme.

Finally, the third research theme concerns institutional and organisational change, with research into evidence-based policy and into learning from disasters making up the last two of the eight research areas identified.

The report then dives into some detail on more than 70 examples of research topics that fit within these eight priority areas. These will certainly help researchers see where their specific research interests and expertise may fit (see below, and in the NHRA Research Priorities quick reference spreadsheet).

More broadly, however, it is worth lingering on three key takeaway messages that set the NHRA Research Priorities a little apart and ahead of some other past reports.

No More Natural Disasters

The language around hazards, risks, and disasters has been subtly evolving for several years now. One important distinction cemented since the Sendai Framework was published in 2015 is that there is no such thing as a “natural disaster”. Disasters only happen through the interaction between human activities and the existence of natural hazards, such as bushfires, floods, storms, and heatwaves. So, a natural hazard may be a cause of a disaster; but the disaster itself is not natural, in the sense that human decisions and activities are also essential causes.

This subtle but important shift is at the core of not only the language in the NHRA report, but also the identified Research Priorities. Natural hazards are an inherent and enduring feature of the Australian environment. Past human decisions have led to increasing frequency and severity of those natural hazards. But the emphasis of the research priorities is firmly on future human decisions and responses, and what Australian society and Australian institutions need to do to understand, mitigate, and adapt.

For example, the priorities explicitly acknowledge the importance of a consensus-based “social licence” for future action, acknowledging the reality that in a diverse society different sectors will judge risk differently. It is then disaster risk reduction and disaster resilience, rather than natural hazards themselves, that are the primary research priorities for NHRA.

Lifelines rather than Critical Infrastructure

Critical infrastructure, such as utilities networks, supply chains, and communications, plays a vital role in both disaster risk reduction and disaster resilience. Unsurprisingly, critical infrastructure-related research has a high profile under both the foundational and functional research themes. But another subtle change in language begins to shift the emphasis away from an explicit focus on critical infrastructure, towards a perspective of critical infrastructure in the context of the investment and policies that underpin it, and the people who rely on it.

The terms “lifelines” and “lifelines services” are increasingly being used to capture this more holistic, integrated, end-to-end perspective on critical infrastructure. How people plan, resource, and use critical infrastructure is at least as important as the infrastructure itself. While the term only appears once in the Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements, it resonates strongly with that report’s idea of a system of “unbroken linkages”, connecting government to community, and decision makers to those affected by decisions. Research that isolates any one link of this chain, such as focusing on specific infrastructure to the exclusion of how the infrastructure supports resilience, risks losing clarity on what it is that makes that link so important.

Traditional Knowledge and Indigenous Researchers

A third key message woven throughout the NHRA Research Priorities is the fundamental relevance of Traditional Knowledges in effective disaster risk reduction and lasting disaster resilience. The priorities are explicit about the value embedded in the wealth of insights from Indigenous Science, to date largely ignored by the dominant Western scientific traditions.

The report also highlights the need to understand the interactions between disasters and a person’s social, economic, and cultural background in disaster resilience research. Understanding the ways that disasters can disproportionately impact disadvantaged sectors of society, including Indigenous communities, is naturally a recurring priority in several research topics.

But in one further subtle shift, the report foregrounds the role not only of Indigenous Science, but of First Nations scientists in the pursuit of disaster resilience and risk reduction research. First Nations researchers are themselves an integral part of the research effort needed to overcome the challenges society faces. In this way, the report serves as a timely reminder to all of us that First Nations people are just as vital to success in searching for innovative solutions, as they are to the urgent need to find those solutions.

Share this post