The UK Government has been actively prioritising Geospatial science and technology for many years. We’ve seen this, for example, with the establishment of the UK Geospatial Commission in 2018 within the UK Cabinet Office, set within the wider context of the UK Government’s stated ambition for the country to be an acknowledged “global science and technology superpower”.1

On June 15, 2023, the Geospatial Commission released the UK Geospatial Strategy 2030: Unlocking the Power of Location. So what’s new in the strategy? And what might countries like Australia might learn from the UK’s experiences?

Four plus one equals three

The new Geospatial Strategy is an update of the UK’s first ever Geospatial Strategy, released in 20202. The new strategy is structured around three objectives or “missions”3. Two objectives are strongly based on aggregates of the original (four) objectives in the 2020 strategy. The third objective appears substantially new to 2023 (i.e., 4 original plus 1 new have been reorganised into 3 updated objectives).

Application focus

Starting from the middle, the second of the three Strategy objectives is all about growing the applications of geospatial intelligence (“Drive greater use of geospatial applications and insights …”, pp. 36–42). Location data is a “critical national asset” and the Strategy fundamentally recognises the value of location for supporting decisions in every sector of industry, every department of government, and every corner of society. Applications were a prominent theme in the original 2020 Strategy (captured in two of the 2020 “missions”—“Promote and safeguard the use of location data” and “Improve access to better location data”) and remain perhaps the most predictable inclusion in the updated Strategy.

Ecosystem focus

In contrast, perhaps one of the most eye-catching developments in the new 2023 Geospatial Strategy is the emergence of the geospatial ecosystem as a central theme (“Build confidence in the future geospatial ecosystem”, pp. 43–47). The new ecosystem-focus draws strongly on two of the 2020 Strategy “missions” (namely “Enhance capabilities, skills and awareness” and “Enable innovation”), but explicitly recognises that spatial industries, capabilities, and skills are but some of the ingredients in a successful national geospatial strategy. Instead, the 2023 Strategy attempts to position geospatial within a much larger web of technologies, sectors, expertise, innovations, policies and priorities.

This recognition—in a nutshell, that spatial is special … but not that special—is a significant evolution in the updated Strategy (even if occasional atavisms are still evident, such as in the figure below, not unlike ones that might be found in any GIS textbook from the past 40 years). While the timbre of the “geospatial ecosystem” focus is new to 2023, this emphasis echoes a key theme also found in the recent UN-GGIM/Geospatial World Geospatial Knowledge Infrastructure Report, and can still be heard, if faintly, in the 2020 UK Geospatial Strategy (which explicitly mentions “geospatial ecosystem” once, for example, albeit in contrast to more than 40 mentions in 2023).

Technology focus

Continuing the theme of a rapidly evolving geospatial ecosystem, the updated 2023 Strategy has a widened focus on enabling technologies (“Embrace enabling technologies to accelerate geospatial innovation”, pp. 32–35). New space-based remote sensing and Earth observation (EO) capabilities appear most prominently amongst the identified enabling technologies (even though the narrative somewhat paradoxically leads with an image of the recently decommissioned SPOT-7 satellite, p. 11). AI, deep learning, and cloud computing are also woven throughout this discussion, especially in combination with space-based data, as one might expect. However, there are some notable omissions from the enabling technologies identified, which might also have included many other current technologies, such as IoT and immersive AR/VR interfaces, and emerging technologies, such as blockchain proof of location and quantum inertial sensors, to name but a few.

What can we learn from the Geospatial Strategy?

The clearest shift in emphasis in the updated UK Geospatial Strategy is in the emergence of the “geospatial ecosystem” at the centre of the discussion. This wider focus—not only on spatial industries, spatial technologies, spatial skills—can be seen as part of the healthy maturation for an area, as it becomes integrated rather than isolated, special but not solitary.

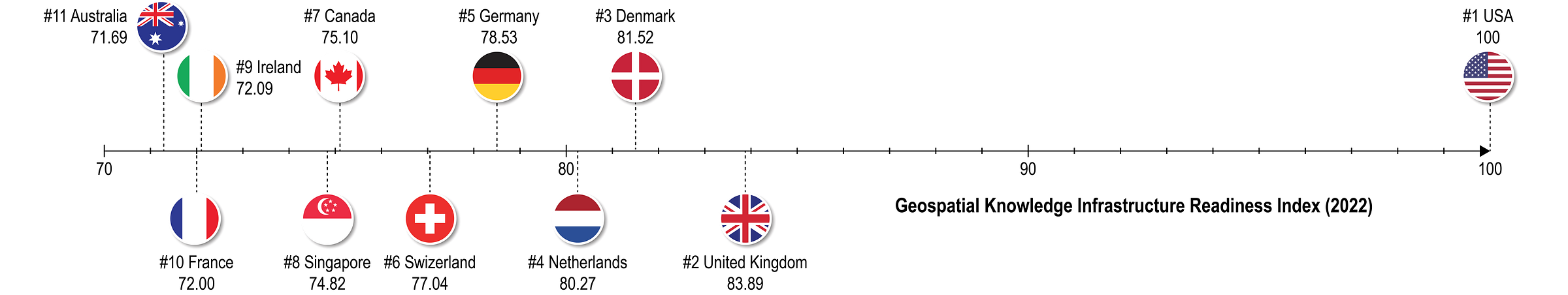

We can see the beginnings of similar realignment and integration in other places too, for example, in the active attempts to advance a Space + Spatial agenda here in Australia. The Strategy also gives clear indications of crossing not just sector boundaries, but also international boundaries, with the UK’s evident ambition to be a recognised world leader in Geospatial. The UK was ranked second in the world for “geospatial readiness” in the recent UN-GGIM/Geospatial World Geospatial Knowledge Infrastructure Report (as the report reminds us on more than one occasion!). Australia ranked just outside the top 10 (see below).

Other secondary themes, such as critical infrastructure, climate adaptation, digital transformation, education, and research and innovation are woven through the strategy as one might expect. But, here too are some conspicuous omissions, which seem important to address in future developments. One of the most obvious omissions is the lack of any real profile or priority for diversity and inclusion in the Strategy. It’s hard to imagine a country becoming a “global superpower” in geospatial science and technology with large swathes of its potential workforce excluded. Yet we know that an inclusive and equitable space and spatial industry is many many years away, both from systematic studies of the sector as well as high profile instances of documented failures. By contrast, the Australian Space Agency has committed itself to leading the initiative to make diversity and inclusion a priority in the Australian space industry.

More subtly, despite the welcome shift to the language of a “geospatial ecosystem”, the Strategy focus remains primarily technocratic, with limited room in that ecosystem for connections to the lived experiences of the people who our technologies and governments must serve. For example, while the Strategy gives a nod to privacy and ethics4, it expends much more effort in celebrating the burgeoning location intelligence industry. This shadowy and poorly regulated multi-billion dollar geospatial industry harvests, aggregates, and resells individual location data from our phones and other location-aware personal devices. The industry is undoubtedly of massive societal as well as economic value, but equally undoubtedly raises serious privacy and safety concerns that are today still barely regulated or controlled.

So while I hope future geospatial strategies, whether in the UK, Australia, or around the world, will go further in extending the geospatial ecosystem to include the citizens whose lives are increasingly impacted by Geospatial, the 2023 UK Geospatial Strategy undoubtedly marks an important milestone for the sector globally.

UK Government (2023) “Plan to forge a better Britain through science and technology unveiled”, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/plan-to-forge-a-better-britain-through-science-and-technology-unveiled

The UK Geospatial Commission (2020) “Unlocking the Power of Location: The UK’s Geospatial Strategy 2020 to 2025”, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/894755/Geospatial_Strategy.pdf

To me, the Geospatial Strategy “missions” read as objectives, and certainly not as “missions” in the sense of “mission-oriented innovation”.

To my mind, a cursory and arguably fundamentally flawed nod, at that. In the Strategy’s “ABC of ethical use“ of location data, the Geospatial Commission appears to have swept aside some of the most longstanding elements of fair information practices, including consent (where citizens retain the ability to withhold consent for their location data to be used at all) and use limitation (where citizens’ data can only be used for the previously stated purposes for which it was collected).

Share this post